|

[Historical

Background]

[Eastern Jews' Mass Migration] [Parliamentary Debates - Western & eastern Jews] [The Specter of Jewish World Rule] [Was Young hitler Anti-semite?] [Two examples] [Transports (of Porges) from Vienna to KZ Camps]

Historical Background Around 1150, when the dukes of Babenberg made Vienna their residence, they brought Jews into the city, who settled in the area of today's Judenplatz (Jew square), worked as money lenders and tradespeople, and enjoyed the sovereigns' special protection-paying considerable taxes in return. As early as 1200 Vienna had its first synagogue. Over the course of the centuries, there were intermittent phases of expulsion, "Jewish auto-da-fes," and resettlements. The situation became particularly dangerous at the time of the Turkish Wars in the seventies century, when religious fanaticism was by no means directed only at the Turks but at the native Jews as well. In 1623 the 130 Jewish families in Vienna were banned from the inner city and forcefully resettled in a new ghetto between the forks of the Danube. At the instigation of his Spanish wife Margarita Teresa, Emperor Leopold I had all Jews expelled in 1670. They lost their property and all valuables, were only allowed to take with them what they could carry , and had to consider themselves lucky that they did not lose their lives. The Viennese set fire to the synagogue and in its place erected a church dedicated to the Emperor's saint. The ghetto turned into a new Catholic suburb, Leopoldstadt. Only a few years later the emperor, now a widower and in need of money, brought the Jews back to Vienna. They again settled in what was now Leopoldstadt, which was soon scornfully nicknamed "Matzohville." As late as 1900 approximately one third of all Viennese Jews lived there. The Christian Socials compared the existential battle between the Christian Occident and the heathen Turks to the "defense battle" against the Jews. Thus during the mayoral campaign of 1895 Lueger shouted: "Today is the memorable day of Vienna's liberation from the Turks, and let's hope that we … can avert a danger from us that is greater than the Turkish threat : the Jewish threat." According to a newspaper report, the speech was followed by "thundering applause and endless shouts of "Bravo!'" Modem anti-Semitism hit the Jews in Austro-Hungary in what was probably the happiest phase in their history .After centuries of oppression, the liberal national basic law of 1867 had brought them equal rights, completely and without qualification. Now they could finally enjoy all those large and small liberties that had been denied them for centuries. They were allowed to own property in the capital, could choose where they wanted to live, become governmental civil servants, attend universities without restrictions, and more. An immediate consequence of emancipation was a wave of Jewish immigrants into the capital and imperial residence. Before the emancipation, in 1860, 6,200 Jews lived in Vienna, which represented a 2.2 percent share of the population; in 1870, there were 40,200 Jews, which was 6.6 percent; in 1880 the numbers were 72,600 and 10.1 percent, respectively. In 1890 Vienna had 118,500 Jews who, however, after the incorporation of the suburbs, only represented 8.7 percent. This percentage remained a constant in the rapidly growing city. In 1900, 147,000, and in 1910, 175,300 Jews lived in Vienna - religious Jews, to be sure. Following the criterion of ethnic anti-Semitism, which had become popular by then - that is to say, including assimilated and baptized Jews - the numbers were much larger. Most of these 175,300 religious Jews, 122,930, were part of the German share of the population, including the Eastern Jews, whose Yiddish was regarded as German. According to their everyday language, the rest were Poles, Czechs, Romanians, and others. The 51,509 Jews in Vienna who were registered as "aliens" were mostly Hungarians. These statistics do not reveal how large the share of Russian Jews was, for most of the refugees had not settled yet and were not included in any statistic. Among the Dual Monarchy's cities, Vienna had by no means the largest share of Jews. In Cracaw they represented 50 percent, in Lernberg and Budapest, 25 percent, and in Prague, 10 percent. Compared to other large cities in Europe, however, Vienna's share was very high. The Jewish share in Berlin was between 4 and 5 percent, and in Hamburg 2 to 3 percent. The euphoria triggered by the freedom the immigrants had finally achieved, motivated many of them to great achievements. All doors seemed to be open to those who worked hard. Emancipation fanned their desire to become respected members of society by way of achievement and education. In the Catholic-conservative atmosphere of Vienna, which was still largely characterized by bourgeois complacency and had a hard time dealing with the innovations of the modem age, the Jews who were education-conscious and eager for success encountered little competition. The writer Jakob Wassermann, for example, who had immigrated from Berlin, noted this with astonishment. The nobility , he observed, which had formerly been the leading social class, was "entirely indifferent": it "not only kept cautiously away from intellectual and artistic life, but was also afraid of it and despised it. The few patrician bourgeois families imitated the nobility; an autochthonous bourgeoisie no longer existed, and the gap was filled by civil servants, officers, and professors; below them was the closed bloc of the petit bourgeoisie." In short : "The court, the petit bourgeoisie, and the Jews gave the city its character. That the Jews as the most mobile group kept all the other groups constantly on the move, is no longer astonishing.

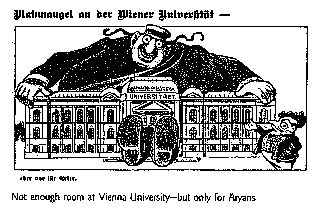

Although if theology is excluded only 5.3 percent of altogether ten thousand Christians attended university between 1898 and 1902, the figure among Jews was 24.5 percent. Jewish students made up almost one third of all university students in Vienna. Jewish students' preferred majors were medicine - in 1913, they constituted more than 40 percent of all students of medicine in Vienna - and law: in 1913 more than one quarter of all law students were Jewish. Jews preferred the independent professions of lawyer and doctor. Of altogether 681 lawyers in Vienna in 1889, more than half -394- were Jewish. Twenty years before, there were only thirty-three. In Cisleithania, most Jews adopted the dominant nationality, at least culturally and economically: German. They loved German language and culture, were enthusiastic about Richard Wagner, whose most modern interpreter was Gustav Mahler, and felt themselves to be German- Austrians. Between 1867 and 1914 Vienna became a metropolis of modern art and science, especially in the fruitful symbiosis of Viennese and Jewish elements. There were spectacular success stories in trade and economy, such as that of department store king Alfred Gerngross, which after his death in 1908 was told everywhere. Having emigrated from Frankfurt to Vienna with his brother in 1881, he opened up a fabric store, then bought one house after the other on Vienna's largest business street, Mariahilfer Strasse, and built a huge department store. He left his eight children a fortune of more than four million kronen. Those craftsmen whom Hitler knew personally as buyers of his pictures were successful too : frame-maker Jakob Altenberg from Galicia, glazier Samuel Morgenstern from Hungary. "Jewish intelligence" became a standing expression in Vienna around 1900. The writer Hermann Bahr joked that every aristocrat "who is a little bit smart or has some kind of talent, is immediately considered a Jew; they have no other explanation for it." Although Gustav Mahler had been baptized long before, Alfred Roller believed he could detect in his friend a downright "Jewish" compulsion to work hard : Mahler never hid his Jewish background. But it didn't give him joy. It motivated and urged him on to higher, purer achievements. "Like when someone is born with one arm too short: then the other arm has to learn to accomplish even more and eventually perhaps accomplishes things that both healthy arms couldn't have achieved. That's how he once explained to me the effect of his background on his work." The growing social reputation of Jews who had become rich found its expression in mansions on the Ring Boulevard, which were as if in competition with the palaces of the old nobility, in the medals and titles which the emperor bestowed on them in return for their accomplishments and generous donations, and in spectacular marriages of rich Jewish women with impoverished aristocrats. The solution to the Jewish question, which was thousands of years old, finally seemed to be in sight in the form of total assimilation, including conversions and mixed marriages. In this respect, however, there were obstacles to overcome. Mixed marriages between religious Jews and religious Christians were prohibited. In order to get married, one of the partners either had to convert to the faith of the other or declare himself or herself unaffiliated with any church. Either step was usually taken by the Jewish partner. Between 1911 and 1914 such marriages occurred almost ten times as frequently as marriages between Catholics and Protestants. Politically the Jews tended to be in the liberal or Social Democratic camp, as Representative Benno Straucher emphasized in the Reichsrat in 1908: "We Jews were, are, and will remain democratic, we can only flourish in democratic air, for us, reactionary air is stuffy, we subscribe to a free, democratic weltanschauung, therefore we can only pursue truly liberal policies." This did not mean that they agreed on party politics. The Zionist National-Zeitung complained in 1908 : "The fourteen Jews in Parliament are members of five different parties." Only the four Zionists and one "Jewish Democrat" were openly Jewish, the others were Social Democrats or in the liberal camp. Of the six Jewish deputies from Galicia, for example, three were Zionists -that is to say, nationalist Jews- the other three were Social Democrats. The success of Jewish immigrants aroused jealousy and hatred in those native residents who were left behind by the sudden competition and could not deal with the modern era's innovations: the craftsmen who lost their livelihood to the factories, the store owners who were put at a disadvantage by the department stores. Only six years after emancipation, during the crash of 1873, a new wave of anti-Semitism was vented against the "capitalists," the "liberals," and the "stock exchange Jews." In 1876 a storm started brewing at the universities, which was triggered by the famous professor of medicine Theodor Billroth's criticism of what he considered the disproportionately large share of Jewish medical students from Hungary and Galicia. Billroth questioned the success of assimilation, arguing "that the Jews are a sharply defined nation, and that no Jew, just like no Iranian, Frenchman, or New Zealander, or an African can ever become a German; what they call Jewish-Germans are simply nothing but Jews who happen to speak German and happened to receive their education in Germany, even if they write literature and think in the German language more beautifully and better than many a genuine Germanic native. "Therefore [we should] neither expect nor want the Jews ever to become true Germans in the sense that during national battles they feel the way we Germans do." Those Jews who had immigrated from the eastern countries, he argued, were lacking "our German sentiments," which were based on "medieval Romanticism." Billroth admitted that inside, "even though I have reflected about this a great deal and do like some of them individually," he still felt "the gap between purely German and purely Jewish blood to be just as wide as the gap a Teuton may have felt between himself and a Phoenician." Now the German fraternities felt authorized to expel their Jewish fellow students. The fraternity Teutonia introduced the "Aryan Clause" as early as 1877" and the other fraternities followed suit. The fraternities justified their actions with an appeal to the Berlin philosopher Eugen Dühring and his much-quoted remark: "The German students must regard it as their honor that the sciences are presented to them-or rather, bungled and contaminated in a Jewish way" and traded off-not by an alien and much inferior race which is entirely incapable of serious science." |

<< Next chapter >>