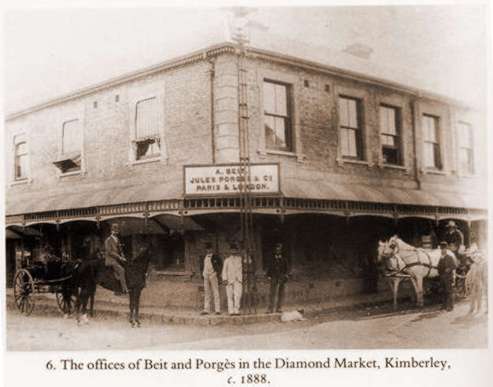

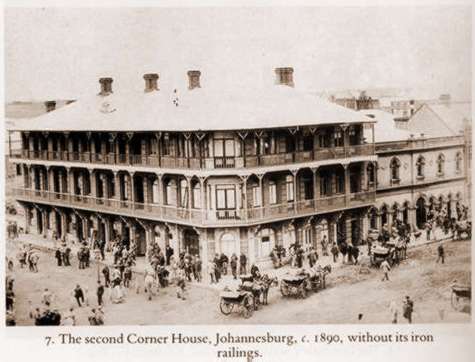

It would indeed have been uncharacteristic of Julius if he had avoided talking business with Porgès, even on his honeymoon. Business was his world, and for years to come Birdie was forced to accept this. In any case Porgès had to plan another visit to Africa. More capital was needed urgently for investing in heavy machinery on the Rand, and here the key figure in Paris to be won over was Rodolphe Kann, now a considerable friend of Julius. Another matter for discussion was Beit's return to Europe as a full partner in the firm, which would involve changes in structure and responsibilities. Rodolphe Kann and his brother Maurice were originally from Frankfurt. Through them Julius became interested in collecting Italian Renaissance bronzes. Since he also was beginning to acquire Flemish and Dutch paintings, the Kanns suggested that, like Porgès, he should seek the help of Dr Wilhelm von Bode, at that time assistant keeper of the sculpture and paintings department at the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin and later to be that museum's celebrated director-general. Julius seems to have made a start by actually buying and offering to the museum two very acceptable Flemish pictures, dated about 1500. In his letter to Bode Julius said that although he lived in England "part of his heart" was still in Germany. The Wernhers had moved into a pretty mid-Victorian house, which the amused Rodolphe Kann called "bijou", 38a Porchester Terrace in Bayswater, not far from Birdie's mother. In those rather heavily furnished rooms, with plenty of draperies and curtains, potted palms and ostrich feathers in vases, space for objects of art must have been limited, so it is something of a surprise to learn that in 1890 Julius whilst in Berlin bought the splendid (about three foot six inches high) late fifteenth-century Spanish picture St Michael and the Dragon, by Bartolome Bermejo. This masterpiece, originally from the church at Tous, near Valencia, was to prove one of the most important pictures in his entire collection. No doubt Bode recommended it because of its rarity, and very likely it had been turned down by the museum. The Flemish influence is obvious in the style, and the dragon is certainly bizarre, like something dreamed up by Hieronymus Bosch, but the glowing colours and the gilding, and the richness of the details, including the depiction of jewels, must have appealed strongly to Julius. Even so, the final effect is awesome, and one cannot quite visualize it hanging in Birdie's drawing-room at 38a Porchester Terrace. It was said to have been in a bad condition, and no doubt was thus considered a satisfactory bargain. Bode meanwhile had been in London and had been introduced by Julius to Beit, who had invited him to stay in his rooms at Ryder Street. He was a shy man and thus obviously felt at ease with Beit. For many years thereafter he helped him and, to a certain extent, Julius in building up their enormous art collections. Beit's first major acquisition was The Milkmaid by Nicolas Maes. Bode also acted as a dealer, and in his autobiography claimed that he was able to secure several masterpieces for Beit at specially low prices. The tradition is that he did not charge a commission; even if this were true, which seems unlikely, Beit in his typically generous way would surely have compensated him somehow. Bode admitted frankly that he hoped his clients would support the Kaiser Friedrich, and both Beit and Julius obliged with gifts of money and pictures. But there were grumbles about the Kanns, who bought at auction and would only afterwards consult Bode about values, thus avoiding paying a commission. There were hints that they might instead remember the museum in their wills, but unluckily this never came to pass. Beit's arrival in London from Africa had been delayed, partly because of developments on the Rand, partly because of unrest at Kimberley, where commercial decline and unemployment were being blamed on De Beers Consolidated. Early in June effigies of Rhodes, Beit and Barnato were burnt outside the De Beers offices. This was followed by the horrific disaster of a fire in the De Beers Mine, involving the deaths of a third of the workers. Kimberley was now far from being a mere frontier outpost. Its gabled and fretworked houses were not unlike Simla in India; it had become a metropolis, "respectable", what with the arrival at long last of the railway, and the installation of electric street lighting, the first in South Africa. But the amalgamation of the mines had meant redundancies, and white workers were being left destitute. The rich were being tempted away to Johannesburg, which in spite of its discomforts was being systematically planned in bricks and mortar. Shopkeepers and merchants at Kimberley were also feeling the effect of the "closed compound" system for black workers, once strongly promoted by Julius Wernher among others as a way of combating IDB: workers, when not in the mines, were kept shut in a kind of fortified area with its own shops, baths and eating-houses, from the moment of their arrival until their departure months later. No alcohol was allowed. Blacks were also being subjected to humiliating body searches after work. They were stripped naked, every orifice being probed, even open sores, and their hair, armpits and spaces between the toes minutely examined. Even more unpleasantly, they were purged with castor oil in case diamonds had been swallowed. And it has to be admitted that these last methods did produce some dramatic results. On a yearly average 100,000 carats worth were recovered until 1901. A certain amount of the De Beers work-force was convict labour: another saving. The mortality rate in the closed compounds was high. These compounds have been seen as a crucial development in South African labour relationships. Julius had succeeded in arousing Rodolphe Kann's interest in the Rand, and Jim Taylor was asked to follow this up with a "seductive" selling letter. "There can be no doubt," Taylor therefore wrote to Kann, "about the ultimate success of the gold industry on the Rand. It is only a question of time, energy, practical mining and the investment of more capital... Two years ago not a hole had been made and there was no habitation anywhere on the Main Reef. The district was populated by a few hundred farmers who owned nothing but the land they lived on and who subsisted on the produce they raised from their lands." Now, he said, there were 3,000 houses and 1,700 inhabitants. (By 1892 the total population of Johannesburg was estimated at 21,715, of which 15,005 were white.) Kann had no need to be told that the mining of gold was quite different to that of diamonds, and that the problem of IDB did not exist. On their arrival at Johannesburg Eckstein and Taylor had erected a temporary wooden office on the corner of Commissioner and Simmonds streets, but this was to be reconstructed in brick in 1889, and later elaborately faced with ironwork. Whether fortuitously or, more likely, by design, it faced the Stock Exchange, already an imposing structure and designed to be permanent, though, as it happened, much of the dealing was done out of doors in a chained-off area between the two buildings. Known as the Corner House (partly a play on the German meaning of Eckstein's name), it was to become famous in the future city not only as a landmark but as the seat of a great dominion that controlled the world's richest goldmines, and much else besides. In 1904 the Corner House was rebuilt yet again, appropriately the tallest building in Johannesburg.

In spite of occasional glooms there was little doubt about the eventual importance of this ridge in the heart of southern Africa. By 1894 a railway connection had been laid to Pretoria from Delagoa Bay. There was a racecourse at Johannesburg. A fine new clubhouse, the Wanderers, had been built, fit for tycoons and magnates. "What a future there is before us in South Africa!" wrote the mining engineer Theodore Reunert. A vast country waking up, as it were, from the sleep of ages, and realising all at once that it is destined to playa great part in the world. A superb climate, a fertile soil, boundless mineral wealth, and, all round, millions of idle hands waiting to be employed in its extraction." To which some could only utter Amen. Flora Shaw, the brilliant journalist and admirer of Rhodes, thought Johannesburg "hideous and detestable", without taste or dignity, dusty in the winter, a quagmire in the summer. To Barney Barnato's cousin Lou Cohen it was a place where men smoked like Sheffield and drank like Glasgow, and where the air was perfumed with the odour of barmaids, who knew their prices. The historian A. L. Rowse had two Cornish miner uncles who died at Johannesburg, one crushed to death by a skip let fall by a drunken engine driver. In his childhood Rowse used to hear of the "raw horror" and the gin palaces of Johannesburg where concertinas provided the favourite music and the dust from the mines clogged the lungs. By 1895 there were ninety-seven brothels in central Johannesburg. Julius Wernher had been responsible for giving the firm a name for fair play, and Eckstein and Taylor were expected to maintain this at Johannesburg. The Corner House acted as a holding finance company for the mines they floated. Each mine had its own directors and management, but the firm had control over appointments and major decisions. Hermann Eckstein's biographers have described him as human, lovable and dynamic, with a skill in "frenzied negotiations" while still maintaining an equable temperament. His portraits show a pleasant bearded face and smart, well-cut clothes, and his wife has gone down in history as having been the prettiest girl in Kimberley. But an equable temperament did not help Eckstein's chronic insomnia and other nervous ailments. He was without any doubt an immensely respected figure in the South African financial and mining community, and was given the 'unquestioning support' of his superiors in Europe with virtually unlimited credit. Soon regarded as Johannesburg's First Citizen, he was the natural choice as first President of the Chamber of Mines. The policies of the Chamber of Mines, it need hardly be added, on such matters as the control of wages and the organization and flow of the "millions of idle hands" came almost to be equated with those of the Corner House. Julius was three years younger than Eckstein. Their Lutheran upbringing was something in common, but Eckstein's meticulous habits and formidable energy appealed to him far more. Then there was that bond, shared with Beit, of having roughed it together at Kimberley. The Corner House partners kept one-fifth of the profits and were free to invest on their own accounts. The rest of the profits went to London. Every week Eckstein wrote a long letter to 29 Holborn Viaduct, so detailed that business colleagues and rivals were amazed by Julius's intimate knowledge of the topography of the Rand, which of course he had never seen, and its personalities, even its gossip. Eckstein also strove to keep the firm out of politics, knowing Julius's attitude. He used to say that whenever someone came into the office and talked politics he would see Julius's face on the blotting paper before him. Originally Porgès and Julius had been nervous of seeming to be too closely allied with the controversial J. B. Robinson, so the Johannesburg office became known simply as "H. Eckstein". Taylor was still in his twenties, six feet tall and South African born, regarded as an excellent mixer; "he knew everybody by their first names." Eventually he became based in Pretoria when it became important for the firm to be in more direct touch with the government and in particular the wily old President, Paul Kruger, whom Carl Meyer of Rothschilds aptly described as a "queer old Boer, ugly, badly dressed and ill-mannered, but a splendid type all the same and a very impressive speaker". Kruger was, unfortunately, a man of very little education, in spite of his intelligence, with a literal belief in the Old Testament, and convinced even that the world was flat. One of the first companies to be floated by H. Eckstein was the Robinson Gold Mining Company, named -naturally- after the "steely eyed" J. B. Robinson and registered in February 1888. The Robinson Syndicate owned a half share of claims pegged out by a certain Japie de Villiers. Claims on the Rand were much larger than at Kimberley: 150 by 400 Cape feet, approximately one and a half acres. It was the brilliant young Taylor who had spotted the capabilities of that mine: five to eight ounces out of a ton of crushed banket. Robinson had bought the half share for £1,000 but Villiers wanted £10,000 for the rest, which he did receive, though in shares (later to be bought back by H. Eckstein for £80,000). Shortly afterwards other companies and syndicates were floated in order to develop holdings, such as the Randfontein Estates Gold mining Company, the Modderfontein and Ferreira Companies, to mention a few of the largest. Then J. B. Robinson was persuaded, without much difficulty, to sell his share of the Robinson Syndicate for what then seemed to be the astonishing sum of £250,000. He moved on to the West Rand, but came to realize that he had made a mistake, and considered that he had been swindled by Beit, who thereupon (with all his partners) was listed as an arch-enemy. It was reckoned that over the years the properties of the former Robinson Syndicate were to earn the firm over £100 million. All the same, J. B. Robinson was to become one of the world's wealthiest men. In that boom year of 1888 gold production had increased by 10 per cent. The Robinson Mining Company crushed in October 726 tons for 3,551 ounces. In November this total had increased to 4,000 ounces. Eckstein wrote to Julius in October that there was a net profit of £71,000 for the Company "after very considerable writing off and taking in shares at the lowest prices". He added: "We start consequently on a very defined and safe basis, and shall show a very handsome balance at the end of December." Early in 1889 he wrote to say that the net profit for the whole concern in the previous year was £860,505.6s.6d., which "will no doubt be considered satisfactory". "It could easily have been fixed at over £1,000,000, but I preferred my usual rule by taking everything at what I may term safe values." An elaborately secret telegraphic code for "high-priority" deals had perforce to come into operation. Kann arrived at Johannesburg from Paris and was suitably impressed, so much so that he was able to report favourably to financial associates in Europe, notably the Rothschilds of Germany, Austria and France. "In fact," Taylor wrote in his autobiography, "all those who had made money out of the diamond shares became eager to participate in the gold shares." This "broadening of the market" was a vital phase in the expansion of the industry. Rhodes had successfully floated his own company, Gold Fields of South Africa, with a capital of £250, 000. Even if he could not quite compete with Eckstein or Robinson, the company proved extremely lucrative, and he drew for himself one-third of the profits. New properties were acquired and there was some playing around with shares. In 1892 when the company was renamed the Consolidated Gold Fields of South Africa its capital had been increased to £1 1/4 million. And now the Johannesburg scene was enlivened by the appearance of Barney Barnato, at last a Member of the Cape Legislative Assembly (he had campaigned in Kimberley from a carriage drawn by four horses in silver harness). Proclaiming that he was in a "financial Gibraltar", he tried almost desperately to catch up in the buying of properties. "He is awfully jealous of us", wrote Eckstein. Soon Barnato's investments were calculated to be in the region of £2 million, and this precipitated an "orgy" of speculation in South Africa. The telegraph line from the Cape was perpetually jammed with buying orders. Half the male population of Johannesburg, we are told, hung around the Corner House, as if waiting for a pronouncement from an oracle. "If there is anyone in Johannesburg", it was said, "who does not own some scrip in a gold mine, he is considered not quite right in the head." In the midst of such frantic excitement Porgès came to survey the sources of the huge new addition to his wealth. First he went to Kimberley, where there were matters to be settled concerning the London Diamond Syndicate, mostly Julius's brainchild. An enormous diamond, 428 1/2 carats, had been discovered in the De Beers Mine. It was exhibited at the Paris Exposition of 1889. But Porgès missed a much larger diamond, 969 1/2 carats, which was to be found in the Jagersfontein mine in 1893. Porgès found the population of Kimberley dwindling. De Beers was building a model village called Kenilworth for white employees, a counter-part of a sort to the closed compounds for the blacks and again with its own shops. The output of diamonds was having to be restricted, and racial tensions were increasing. Porgès confessed that he left with a feeling of slight gloom. The vibrant atmosphere of Johannesburg was certainly a contrast. He arrived there at a time when the Randfontein Company was about to be floated, with a capital of £2 million in £1 shares, later to be sold for four times as much, with useful profits all round. Predictably, collapse and panic were to follow later in the year. This may have been anticipated by Porgès, who had by then already made the sensational decision to retire from the firm. Perhaps he felt that the empire was becoming altogether too complex and unwieldy. Perhaps, as seems possible, he was worried about his health. Or perhaps, as one would almost prefer to think, he simply decided that he had made enough money and wanted to enjoy it and invest some of it in works of art. Madame Porgès certainly wanted him to build a palace that could compete with the chateaux of the French aristocracy. After all he was still only fifty-one. As it happened, he was to live on well into his eighties, which was much more than could be said of most of his colleagues. He has been regarded as one of the most significant figures in the early development of South Africa's wealth, but even now is thought of as "shadowy". Yet it is not quite true that he "simply disappeared into private life". He kept up several interests in Africa, and was partner in syndicates with Kann and Michel Ephrussi which co-operated with the Corner House. Meanwhile the firm of Jules Porgès and Company was reconstituted on 1 January 1890 under the name of Wernher Beit, the partners being Julius Wernher, Alfred Beit, Max Michaelis and Charles Rube. The hand-over was no gift though. Porgès took with him £750,000 in cash and £1 million in shares. A further £500,000 was deposited with Wernher, Beit, to be paid over the next two years. Wernher, Beit was left with £1 million in cash, diamonds and non-speculative investments, and around £2 million in shares and interests of a non-speculative nature. The newly designated firm remained a private company, with no shares issued to the public. Julius Wernher and Alfred Beit were considered the ideal combination, with Julius the necessary brake on his partner's enthusiasms. Beit was intuitive, daring, while Julius made sure that there were always enough funds for an emergency. It was said that Beit never seemed to mind who joined them in new ventures, but that Julius "viewed some of the new alliances with horror" and was always warning the Corner House not to spread the firm's interests too widely. In many cases Julius proved right, and Beit did get into serious trouble when one of his cousins began forging his signature. Alfred Beit had no desire for fame - unlike Rhodes. But in spite of the alarmingly long hours he spent in the office, he seemed capable of enjoying social life. After all he was now a very eligible bachelor, and on his first return to Johannesburg he gave a ball for a hundred and fifty people. To Percy FitzPatrick he was the "ablest financier South Africa has ever known". As always, his energy was prodigious. He built himself a house in Hamburg, and visited Dr Bode in Berlin. In 1891 he trekked with Rhodes (by then Prime Minister of Cape Province) with Lord Randolph Churchill up to Mashonaland, part of what soon was to be known as Rhodesia. He also accompanied Rhodes to Cairo. Julius Wernher, so Taylor thought, would have been the perfect Chancellor of the Exchequer. He gave the City confidence and was described as "blameless". A stranger entering his office was conscious of being in the seat of power and would be afraid of wasting the great man's time. He also loved his home and read a great deal. Those who were allowed into the family's close circle realized that it was a special privilege. The occasional presence of Beit in London did lessen Julius's load of work, and for the first time in years he took holidays, in Scotland and to Dresden or Nuremberg, for instance, and above all he was able to visit his ailing mother in Frankfurt more frequently. Even so his family life suffered. So the time had still not come for Birdie to take to entertaining on the grand scale, or to be launched into the longed-for haut monde. Sometimes there were dinners at Porchester Terrace for international financiers, such as the Rothschilds, Raphaels, Schroeders, Mosenthals and Lipperts, but Julius would also take them to the new Savoy Hotel restaurant. On 7 June 1889 the Wernhers' first child was born, Derrick Julius. Soon afterwards a great shadow fell on their household, which left Birdie "exhausted and broken" and was responsible for a miscarriage. This was the death of her much loved sister Daisy Marc, after long and horrible suffering. Mrs Mankiewicz seemed to go into a decline and "was never happy again". Observing the family's reactions, Julius wrote to his sister Maria, who was coping with their own mother: "One is inclined to doubt His goodness when one sees such tragedies." But Derrick was always the great consolation. His doting parents called him Sweetface, and he was indeed beautiful as a baby, chubby with curly, dark hair. As he grew older, he was dressed in Fauntleroy suits, and it was obvious that he had a quick brain. The second son, Harold Augustus, was born on 16 January 1893, and the third and last, Alexander Pigott, on 18 January 1897. But Derrick was the favourite and consequently spoilt. He was to cause his father a lot of pain. Under the circumstances Julius's letter to Birdie about Derrick, written on 29 September 1891, is worth quoting: The great fear is how he will turn out, and you know my ideas! I would not like a child of mine to be a useless self indulgent idler simply because he is left so much a year - my pride would be to have a man as a son who will take his place in the world! As it happened, the son whom he thought the least intelligent, Harold, was the one who followed most closely in his footsteps as an outstanding man of business. Julius, on a visit to his mother, missed the State visit of the new German Emperor, William II, but insisted that Birdie should watch the procession. On his way home he went to Paris to buy pictures. It was the centenary of the French Revolution and he climbed the Eiffel Tower. Staying as usual with "Porgi", as he called Porgès, he reported that his old chief's legs were shaky with rheumatism but was amused to watch him gobble up his food - "two smacks and the plate is empty". A couple of years later Julius and Porgès went on a "bachelors' holiday" round Italy: Genoa, Florence, Rome ("the longed for spot of every German for centuries past") and Naples. Madame Porgès corresponded by telegram, but Birdie dutifully kept up a flow of letters. "Porgi shows wonderful endurance", Julius wrote, a comment which seems to show that there had indeed been some worry about health. "He is jolly and chatty, never reads anything, although he bought many French novels and Darwin's Descent of Man. When it is hot he sits in his salon wearing only his red striped under vest. Anyone coming in by mistake would think an acrobat was lodging there." A new crisis hit De Beers, with the discovery in September 1890 of yet another diamond mine only four miles from Kimberley. It was named the Wesselton after the Boer farmer Wessel who had originally owned the site. The secret was kept until February when the place, inevitably, was "rushed". It seemed to be a divine answer to the misery of the poor whites of Kimberley, but Rhodes was determined that it should not be proclaimed a public digging, which would mean the end of the De Beers monopoly. At once he started negotiations for purchase. There were angry demonstrations in protest, and some subtle counter-arguments were produced. How long, for instance, would this mine last? A new independent mine would only mean a fall in the price of diamonds, and De Beers would have to restrict its operations, with more men out of work. A foreign syndicate would move in, which would mean "ruin and disorder". By December, therefore, after various jugglings, the mine was safely under the control of De Beers. Not unexpectedly, we read in Julius's "Notes" that "the firm [Wernher, Beit] was largely instrumental in bringing about the various deals". At Johannesburg there was a lively new addition to the Corner House. This was Lionel Phillips, whose abilities had been spotted by Beit when at Kimberley. [Phillips had arrived at Kimberley in 1875, having walked most of the way there from Cape Town.] Jewish, born in London, and described as "wiry" with "immense energy and tenacity of purpose", he had hoped once to be the manager of De Beers. But Beit's offer was more tempting: £2,500 a year, expenses paid and 10 per cent of the profits from managing the firm's interests in the Nellmapius Syndicate, which owned nearly 2 1/2 million acres, including possible goldmines, in the Transvaal. Phillips arrived at a hectic moment, with Porgès about to retire and the Johannesburg share market in a state of collapse after potential disaster had been discovered in the mines. |