Reminiscences by Moses Porges-Spiro

English translation by Arnold Von der Porten The original manuscript,

in gothic German, is conserved at The Leo Baeck Institute (New York) I

was born on December 22nd, 1781. Just after my 14th year my father called me into his room and asked me in a solemn way if I believed that the Torah's revelations contained all that was necessary for our salvation and eternal happiness here and the life beyond. Until this hour I had been quite a believing Jew, even though doubts and reservations had arisen. He told me in a solemn tone:

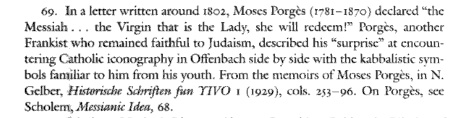

I dissolved into tears, kissed my father's hand countless times and I felt elevated, now belonging to a higher, nobler class of mankind. It would be superfluous to go into the details of the instructions by Kassowitz.What is significant is that he informed me that in recent times a messenger from God, by the name of Jakob Frank of Czenstochau, Polish by birth but who lived quite a while in Turkey, revealed himself as the Messiah. He gathered about him many respected Jewish scholars who believed in him and honored and worshipped him. He acquired a lot of followers whom he captivated by a lot of prophecies, promises of spiritual and physical salvation, and especially an everlasting life. Officials were informed of this and sentenced him to prison so that he spent quite a while in the fortress Czenstochau. Finally released, he became a Christian, as did his family and a great many of his followers. After a while he appeared in Prosznitz in Moravia under the name Baron Frank, in glitter and splendor. He even had a detachment of guards who surrounded his carriage when he went out. It is known that Emperor Josef II visited him there. From Prosznitz he moved to Offenbach where he moved into his own house and gathered about him a great number of his followers, mostly Polish people. he acceptance of another persuasion is an important step. It is of great consequence for the rest of the life of that person. If that step is taken because of conviction, then that step should be termed honorable, but if it is taken because of a delusion by a passion, the goal of which could be reached only by that step, then it must lead to misery and bitter reproach when eventually the passion has dissipated and is followed by calm reasoning.After Frank's death his daughter assumed the leadership of the faithful under the name, "Geriza." [Chewise.] She was no longer young. She was assisted by her two brothers, Roch and Josef. It is impossible to describe the impression this revelation made on me, a young, lively youth in search of truth. The yearning after the "holy camp" in Offenbach took hold of me in such a way that I became restless and had no other thought but to undertake the journey there. However, how could I accomplish this, since I lacked all means and my good father could not provide them? The inducement was prompted by an army recruiting drive in 1798. [Austria, along with most other German States and England went to war against France to quell the effects of the French Revolution of 1789 and the republican zeal. After Napoleon's conquest of most of Europe, that war ended with Napoleon's defeat at the battle of Leipzig on October 18, 1813 and also at Waterloo in 1815.] When young men were being hauled out of their beds at night, it caused me to hide out at an acquaintance's house (Salomon Brandeis). To escape the danger [of conscription,] it was decided after a few weeks that I should emigrate to Germany. [Today Prague is the capital of the Czech Republic. During the time of Moses Porges-Spiro, Prague was the capital of the Austrian province Bohemia. It is interesting to note that he did not consider Austria as part of Germany although the capital of Germany at that time was still Vienna and the Emperor Josef II of Hapsburg was King of Hungary, Emperor of Austria and Emperor of Germany.] Since I could not emigrate legitimately, I was to accompany a merchant by the name of Katz to Teplitz. He was waiting for me in front of the Strachower Gate. When we arrived in Teplitz he directed me to an old Jew from Soboten who spirited me across the mountains along smugglers' paths to Saxony. For this he wanted 2f., a "Species-Taler" [a coin], which I gladly gave him. There I stood on the peak of Geiersberg [Vulture Mountain], a seventeen year old youth, absolutely alone, formerly accustomed to live surrounded by loving parents and siblings being cared for by my mother's gentle ways. Forsaken by everyone, I stood surrounded by forest. I wept, however the goal of my now commenced journey, Offenbach, sustained me. Should the suffering and privations which I was to overcome be the test of my faith in the new teachings? I had been given 60 f. in gold and silver from my family. Besides that I had 3 f. in small coins. Zealous with faith, I vowed to spend only those last 3 f. on my journey to Offenbach, even if I were to go hungry or would have to beg, in order to give the 60 f. as an offering to the Divine Lady, [Geriza/Chewise.] With courage and determination I journeyed on and in the evening I arrived in Fürstenau, a village in Saxony. After a sparse, but much enjoyed, supper, I was given a bed of straw in the large taproom of the inn. Tired, I lay down and was soon asleep. Around midnight a lot of noise suddenly awoke me. A man, (in my fantasy, of giant proportions,) stepped into the taproom with a powerful stick and a pack on his back. Behind him came another one like him and many more, until the room was full. My apprehension and fear were those of an inexperienced youth of seventeen. After an hour the men left the room, having enjoyed a lot of beer and spirits. Later I found out that they were smugglers. In the morning I continued my journey to Dresden. Overnight I rested in a village and around midday I arrived in Dresden. Upon arrival I suffered unpleasantness and insult. I had to pay Jew tax. For the privilege of being born a Jew, just about everywhere in Germany one had to pay body duty, just like the dear cattle. Then my backpack was searched. The customs officer noticed that my sleeping cap had never been used. I had to pay duty on it and a fine [for not declaring it]. That exhausted my small funds. Mr. Jonathan Eibenschuetz had been recommended to me. He was one of us. He was a handsome young man, but he was practically deaf and stuttered. One could hardly understand him. After he had read the letter of recommendation, he kissed me and shook my hand and invited me to be his guest. While I stayed with him in Dresden he housed me and fed me and he procured a passport showing that I was a Saxon subject, so that I would no longer have to pay the miserable Jew tax. I stayed the Easter Holidays in Dresden. When I took leave from Mr. E. this pleasant, kindly man gave me two Reichstaler. [Talers of the realm, quite a bit of pocket money] In glorious spring weather I left Dresden and continued my journey on foot to Offenbach, exhilarated and full of enthusiasm that I was going to reach my goal. At first, because of this elation, I progressed easily even though I had to carry a heavy pack. That evening I arrived in Meissen singing. I enjoyed my supper and slept on a straw bed until early morning, even though my feet hurt and they had open sores. I got up from the bed but I could not walk. I could not even put on my boots. A sad situation when one hurries to such a goal so impatiently. I had no choice but to continue bare foot with swollen, painful feet, on my way to Leipzig. I arrived in front of that city on my third day. The previous nights I had stayed in Oschatz and Wurzen. I was not permitted to go through Leipzig. A policeman escorted me around the town to the road to Weimar. I trudged along that road with difficulty. Tortured by pain and hunger, I lay down in the road feeling discouraged and weak. When I had lain there for about an hour, a carriage from Leipzig came by. As it came near, I pulled myself together and saw that the carriage was empty. I asked the teamster where he was headed.

I

put my pack into the carriage and got inside. It was night when we arrived at Weissenfels. The teamster halted at an hotel. Two waiters, each with a lamp in hand, came out to lift the newly arrived guest out of the carriage. [Carriages in those days had no, or next to no, springs and the roads were unpaved, therefore guests often arrived so stiff that they could not walk unaided for a while.] When they saw me one of them said,

My kindly teamster directed

me there and promised to pick me up early [in the morning.] We traveled all day, except at noon, when we stopped to feed the horses. That night we stayed in a village and the next morning we traveled on. At around 10 a.m. we approached Weimar. Some distance from the town the teamster asked me to get out. After I had pushed out my baggage ahead of me I hesitantly left the carriage. What would the teamster ask for compensation or payment? Apprehensively I asked what I owed. There are no words with which I can express my joyful surprise when this humane teamster asked for 20 kr., with the remark that he only wanted what he had laid out for me. I walked through Weimar [Turenia] without stopping and in the evening I arrived in Gotha. I turned in at an inn, where I had beer and bread. In the adjoining room a table had been set for a large party. It looked very festive. Various roasts, cakes, fruit and various other dishes were laid out. They would be celebrating the baptism of a child. Since I had left Dresden I had not eaten any meat. The food smelled delicious. Then the lady of the house came to me and said, "I see it in your face that you are a child of good parents," and she placed a plate before me with roast meat, eggs and pastry. The next afternoon I arrived at the gates of Erfurt [Turenia]. In those days it had an Austrian garrison. Here I was stopped and ordered to pay 2fl. Jew Tax. No remonstration helped, not even my suggestion that I wouldn't pass through Erfurt. They impounded my baggage. Finally the tax collector acceded to my request to be taken to see the City Captain. A soldier escorted me there. He was not at home, rather he was visiting a Baroness. I requested to be taken there and was admitted. When the City Captain asked me what I wanted, I explained to him how unjust it was to demand 2 fl. tax off a journey-man just travelling through, simply because he happened to be of the Jewish faith. He replied that that was the law of the land. I said to him,

The City Captain kept insisting.

Then the City Captain gave me a written document that exempted me

from all such taxes. Without further adventures, I continued on the road to Offenbach via Eisenach, through Hesse to Hanau, arriving about noon. The hope of reaching Offenbach before evening made me walk very fast. The mood and excitement I experienced is impossible to describe. The meeting of the faithful in Offenbach was called "Mähne" [camp], in remembrance of the camp of the Israelites under Moses. That very day I hoped to arrive at this "Mähne" and be received. In the evening, after dark, I arrived in Offenbach, an open city [i.e. it had no walls or gate.] It was raining. I asked for the Polish Court and was directed to the other end of the city, to a stately house. I was in tears of religious fervor as I entered the holy house. I climbed a few steps and pulled the bell cord. The door was opened. A young man in Turkish garb received me, embraced me and kissed me, called me brother and told me that I was expected. Several Maminim [followers] gathered about me, among them an older Mami [follower] of venerable appearance with already-white hair. He wore the uniform of a colonel and called himself Consky. Consky led me to his room on the second floor. [in North America it would be called the 'third floor' since in Europe the ground-level floor is known as the 'ground floor' followed by 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc.] He assured me that he would always be available to give fatherly advice and support. He instructed me in how to act when I had the expected audience with the holy mother. That very evening many Maminim [followers,] old and young, visited me. The following day I was called to the audience before the Chewise [Divine Lady.] She lived on the first floor. [2nd floor, American] In the antechamber, I was received by a lady-in-waiting. I had to wait for a while. How excited I was and how my heart pounded! Finally the door opened and I entered. I did not dare look into the face of the Chewise. I knelt before her and kissed her foot, as I had been instructed. She spoke a few kindly words, praising my father and praising my resolve to come to the court. When I left I placed my little bag which contained the 60 f. in gold and silver on a table and walked backwards through the door. The impression which the Chewise made on me was favorable, that of an exalted person. Her lovely face expressed kindness, understanding and dignity, her eyes, holiness and enthusiasm. She was advanced in age, yet still lovely in appearance, her hands and feet charming. As I found out later, she had received me with grace. I was assigned to the "Liberia," the highest order, namely with the mostly young people who attend the three high persons at table, and daily when they rode out [in a carriage] and on Sundays in Church. We lived together in one room. This often gave me the opportunity, especially at table, to observe the Masters closely. I was given a hunter's uniform and instead of a hat, a sort of helmet of green leather with metal platelets. It was considered a great honor to be a member of this corps. I often served at table. My place was to stand behind the chair of the Chewise. The hall, where the meals were taken, was fairly large. Three of us were selected to serve the three Masters. Three different ones were detailed each day. After their meal was finished, we ate the leftovers. Since all residents of the house and also those who did not live in the house received their midday meal from the common kitchen and since that meal consisted of vegetables and a very poor quality soup, I enjoyed the leftovers all the more. Every Sunday there was a church parade. We, in uniform, had to take part. My company consisted of members of the sect only. I was drawn especially to the older ones. Among those were many venerable gentlemen, some of them quite old, such as Wolwsky, Dembitzky, Matuschewsky and Ckerwiesky. The young men, especially my roommates, according to their expressions, were very pious, but in the manner of young people, frivolous, and despite the proper form and manners, did not take things too seriously. There was no contact with the opposite sex. Marriage was strictly prohibited. Yes, even one morning a notice was given that anyone who felt a yearning for a woman should ask for 10 lashes with a switch! Almost all of the young men had themselves beaten. At this point I must mention that almost daily visions were reported by the three Masters in turn. These were entered in a book. Copies were made of entries. Every day we were drilled by a Polish drill-master. However, all firearms and sabers were hidden when the French occupied Offenbach in 1799. In the summer of 1798 three sons of Jonas Wehli arrived in Offenbach. With them came my younger brother, Juda Leopold. The Wehlis were well-educated and well-mannered young men. Their names were Abraham, Jontof and Ekiba. They were now given the names Joseph, Ludwig and Max. My brother was given the name Carl the younger. He was seventeen, dependent on others and was instructed to learn to become a barber. In autumn that same year, my good father arrived in the company of Mr. Jonas and Mr. Aron Bur Wehli. I was overcome with joy to see my dear, beloved father again. The three highly respected and learned men were received solemnly and ceremoniously by every one of the Maninim [followers] and the next morning they were received by the high Masters. They laid sacrificial gifts at the feet of the Chewise, the Wehli's in gold, which was received most joyfully. Both were rich people. My good father, who was not a man of means, brought a bolt of batiste. [fine cloth.] This present brought about the beginning of the diminishment of my fanaticism. In the end I became convinced that everything about this place was a fraud and that several hundred well-meaning people were taken advantage of by faked religion, having been drawn here from hundreds of miles around, to become impoverished and unhappy. That same year Mr. Salom Zerkowitz arrived in Offenbach. He had once been quite wealthy. He brought with him quite a fortune, however, he had to offer it up on command. It consisted mostly of Austrian State Papers, which I carried to Frankfurt where I had the old Rothschild convert them to silver. Mr. Zerkowitz was a good, honest man. He cried when he had to give up his last possessions. Next to the dining room was the holy room. In that room were the clothes and the bed of the Holy Father - that is what they called Jakob Frank, the father of the Chewise and her brothers. That room was kept dark, the windows were draped. Here one prayed. In front of the bed, the believers knelt in deepest prayers. You were permitted to go in anytime during the day. In front of the entrance of the divine room, girls were posted as sentries, wearing Amazon dress bearing musket and sword. Usually beautiful young girls were chosen for this duty. As I indicated above, I was hurt by a mocking remark that Joseph made at table in my presence, concerning the present my father had made as it was not very valuable. I felt that one should not judge the man by the value of his gift. From this moment on I started to think and observe. In the beginning I reproached myself for the negative thoughts and considered them sinful. Who was I to doubt what so many worthy and honorable men believed? I entered the holy room and felt remorseful. But soon I found new reasons for more doubt and relapsed. Among the residents of my room there was a young man from Dresden [capital of Saxony] by the name of Johan Hoffinger. He befriended me at this time and after some preparations and sounding, he allowed me to suspect that he did not agree with all of what was going on, or had gone on. When he was satisfied that I would not betray him, he finally confided in me that he had reached the conclusion, after long probing and reasoning, that a fraud of unbelievable proportions was being perpetrated here and that the believers, who had brought such great offerings, could not conceive of the idea that they were the victims of a massive swindle. Also, that they had been robbed of all means by which to return to their far away homes. Through such conversations, which we had quite often, we finally reached the decision to escape. Since we were lacking the means and had no cash at all, Hoffinger suggested using methods that were not honorable nor compatible with the reputation of our families. I therefore wrote to my brother, Dr. Porges, and informed him of my resolve to leave Offenbach. I asked him to let me know of a house in Frankfurt where we would be accepted and where we would receive the means to continue our journey. We were not kept waiting [long] for an answer. The family was delighted with our resolve and directed us to a M. Neustadel in Frankfurt where we would receive money and a friendly stay. Now we could plan our escape in earnest. I informed my brother, [Leopold] of my resolve, showed him the letter from our brother and he at once declared that he wanted to follow me. Now we conspired together as to how we could leave Offenbach. We decided on this course of action because not much earlier a Polish member of the congregation had been caught [trying to leave] and was punished. Since we often had to stand night watch, I was able to arrange that Hoffinger and I would stand watch together. Since we did not have much baggage, all of it could be combined into one bundle. The evening before our flight one of the ladies in waiting summoned me to see the Chewise. It was already getting dark. When I entered the reception room, her favorite dog, a greyhound, which knew me and had never before barked at me, attacked me viciously. The unusual hour for being called and the exceptional attack by the dog frightened me. I believed we had been discovered and betrayed. I fell on my knees. The Chewise admonished the dog saying, "What is wrong with you today? Don't you know my dear Carl? " She then addressed me in Polish, "I have noticed that your uniform is getting shabby. You can go to Frankfurt tomorrow and order a new one for yourself. " She asked me if I had any other desires. I was so moved by her exceptional kindness and grace that I almost confessed everything ruefully. She extended her hand for me to kiss and dismissed me. I was crying when I left her, for I worshipped and loved this high lady. I was nineteen at the time. At midnight I was relieved from my post. I lay down. Around 3 a.m. we got up and wrapped our few pieces of clothing and underwear in a cloth. I avoided taking anything that I had not brought with me. Hoffinger and my brother followed my example. At 4 a.m. I resumed my sentry duty with Hoffinger. We brought our belongings with us. We stood at ground level in the hallway of the living quarters of the Masters Bert and Joseph. When my brother came down the stairs we leaned our muskets into a corner and entered the courtyard with our hearts pounding with the most profound excitement. We were exposed to the danger that the teamster or the stable help might catch us. From there into the garden, we climbed over a [wooden] board wall and were free. This so-called Polish Court lay at the outskirts of the town. We ran towards the nearby forest. We arrived in Frankfurt via Oberrath at around six o'clock. Mr. Neustadel, whose whereabouts we found by questioning, received us very kindly. He let us stay and fed us and gave me the money that he had received from our family. The very same day we obtained clothes for my brothers and me. [The use of the term 'brother' included Hoffinger.] The next morning we took a coach to Seeligens Hof and from there through the Spessart forest to Eselbach, where we stayed overnight. Earlier, we experienced fear of being robbed by several men who came out of the forest in front of the coach. Our teamster stopped the coach and pointed tremblingly at the men who took up positions on the road. Just then we heard the post coach man blow his horn behind us. He quickly came up to us and the men retreated into the forest. We continued our journey to Eselbach in the company of the protecting coach. From home we had been advised to go to Fürth and there wait for further directions. From Eselbach we walked via Würzburg to Fürth. On the road from Eselbach to Würzburg I suddenly felt such a gnawing hunger that weakened me so terribly that I could not continue and I had to lie down. Fortunately some farm women came along and gave me a piece of bread. Later doctors explained to me that if I had not received something to eat then, I would never have gotten up again and I would have perished. When we arrived in Fürth we three took lodging at an inn. Hoffinger was without any means and he was sustained by the money that we had received from our family. I must go into an earlier event. During the night of our flight from Offenbach, Hoffinger committed a dishonest act. He absconded with the key to the safe which Joseph Wehli (Johann Klarenberg) kept under his pillow and also the account book and a book container. [When I discovered this,] I made him hand the book over to me, as he could have used it to make mischief. What Hoffinger had done in Offenbach he repeated in Fürth. During the night he took the above mentioned account book, which I had hidden under my pillow, and he disappeared. He sold the book to a son-in-law of J. Zerkowitz who lived in Fürth. The latter did not make any harmful use of this book. We had letters of recommendation to several gentlemen in Fürth, among them one to Mr. Moses Gosdorf. We were most cordially received by him and invited for dinner. From home we had been advised to remain in Fürth until we received orders to start our journey home. Over the Whitsuntide holidays [the week beginning with Whit Sunday, the seventh Sunday after Easter, also known as Pentecost Sunday] we remained in Fürth [in Bavaria]. After the holidays we were summoned by the police and were ordered to leave Fürth within 48 hours. I found out that this had been initiated by the elders of the Jewish community. Through Mr. Gosdorf, I found out that we were being expelled because I had let myself be shaved with a razor. No remonstrations helped. We had to leave Fürth. We walked to a suburb of Nürnberg since Jews were not permitted to stay in the city proper. From there, we were able to retrieve the letters from home that we had requested to be sent to Fürth. Finally we were advised to start our journey home, which we did at once. When we arrived at the last Bavarian border town, Weithaus, I was given a note not to cross the Austrian border as we would run the risk of being impressed as recruits. We were advised to go to Bayreuth with a letter of recommendation enclosed to a Mr. Enzel. I just want to mention an incident that occurred in Nürnberg's suburb, Gostenhof, while we were having a glass of beer and a buttered slice of bread at midday at an inn. A guest, who was easily recognizable as a Jew, asked whether we were Jews. I said, "yes". Thereupon he cursed us with most profane language, that we should suffer a miserable "Meshune," a disgraceful death, because we ate with a knife and butter from a "Goi." [unflattering word for a non-Jew] I called the landlord and told him that this Jew was cursing us because we were using the landlord's knife, [and I asked] whether it was really so unclean in the inn. Thereupon the landlord grabbed the dear Jew and threw him out. We traveled to Bayreuth at once and arrived there the next morning. Mr. Enzel was a stately, handsome man. He received us kindly and after reading our letter of recommendation, he invited us to live with him. Two beautifully furnished rooms were offered to us and this noble man gave us breakfast, lunch and dinner. He regretted that he could not join us at meal times, as he was in deep mourning over the loss of his wife. She had been beautiful and kindly and he had loved her with all of his heart. He was quite disconsolate. The stay at Mr. Enzel's suited us very well. Our sojourn in Bayreuth was very pleasant. We hardly ever saw Mr. Enzel. After a stay of four weeks, Mr. Enzel sent for me and told me that lack of occupation and idleness is very detrimental for such young people. For that reason he had asked a friend in Hamburg on our behalf, and he had already found employment for us and we could start at once. I thanked him for his well meaning intentions and answered that I first had to obtain the consent of our parents. When that consent was not given, and we were given hope that we could soon return home, I informed Mr. Enzel to that effect. He declared that since we were unwilling to take his well-intentioned suggestion, we should leave his house. He promised to give us a letter of recommendation to Baron W. the owner of the estate Emet near Burgundstadt. He would receive us hospitably, as he was a friend of his. We took to the road. It was during the month of August on a very hot day. Close to midday we passed Burgundstadt. As we approached the city I had taken off my jacket and laid it atop the backpack I was carrying. In the jacket pocket, I had a purse containing about 40 f. From Burgundstadt to Emet one has to climb quite a steep mountain. When we had climbed half the distance, I asked my brother Leopold, who was walking behind me, "Is my jacket still lying on top of the backpack?" "No, you have lost it," he replied. I was thunderstruck. The money in the jacket was all that we had. I threw myself to the ground. My legs could not support me. My brother Leopold ran down the mountain, through Burgundstadt. He asked everyone he met [about the jacket] but without success. He went outside the city gate and someone asked him what he was looking for, and when he answered him, the latter took him to a tanner who had found the jacket. At first the tanner tried to deny that he had seen the jacket. Upon the remonstrations by Leopold, and the explanation as to how unfortunate and miserable we were, the tanner fetched the jacket and the purse was still in the pocket. He had to give a few 'gulden' to the finder. Who can describe my joy when I saw my brother running up the mountain holding the jacket high! That afternoon we reached Emet, a small village. At once I went to the manor house to deliver my letter. I was shown into the garden. There were two gentlemen, one wearing expensive clothes and orders, the other wearing a housecoat. The latter asked me what I wanted. "I have to deliver a letter to the Baron."He took it and broke the seal. The other gentleman came closer, looked at the letter and asked : "Who is the writer who addresses you as `dear friend'?"Embarrassed, the Baron said : "This Enzel is a friend of Minister Hardenberg."The Baron told me to come back the following day. When I arrived the next day, he reprimanded me for giving him Mr. Enzel's letter in the presence of his brother, the Counselor of the Realm. He spoke to me in the Jewish dialect. Finally he said to me : "As a favor to my friend Enzel, who gave you the very best recommendation, I will let you stay here. You can build a house for yourselves, engage in commerce, and also I shall provide a Jewish Beshaiim [cemetery] where you can have yourselves buried."We felt quite abandoned in this little village. There were a few poor Jewish families there, among them a man from Bohemia who was sympathetic to us. Since we said that we expected letters calling us home soon, he gave us advice to take "pletten", namely we, as destitute indigents, should be supported by the Jewish congregation in the area. After persistent repetition of that advice we promised to try it. Our advisor wrote down the names of the settlements where there were Jewish communities. Thereupon we started on our journey. A depressing feeling of shame overcame us at our first attempt. The hosts whom we looked up were mainly cattle dealers and not at home during the week - all were poor people. We were received by the women of the house, given soup and bread in the evening and a place to sleep. In the morning, soup again and a few kreuzer [pennies]. We soon got tired of this and gave up. We received a letter from home that directed us to go to Bamberg to introduce ourselves to the local head of the Jewish congregation, Mr. Abraham Wenzedlitz. This was in the year 1800 in September. We were approaching the theater of war. The French had passed Regensburg and the Austrians stood in Bamberg. The villages through which we traveled were occupied by Austrian soldiers. Late in the evening we arrived at a fairly large village near Bamberg. We wanted to turn in at the first guest house but we were not admitted. The same thing happened at the second one. When we were also turned back by the third guest house - it was an old man - we pointed out to him what a wicked deed it was to abandon us to the night and bad weather. Finally after our long entreaties he said that we were French spies. He did not believe our assurances that we were Austrians. Now we told him : "We are Jews." "Show me the Ten Commandments."We could not show them to him as we did not have them. There upon the landlord brought out a loaf of bread. "What do you call this in Hebrew?" "Lechem," I said, and the good old man was satisfied. We

relieved our hunger and thirst with lechem, butter and beer. At that time we had received a letter from home instructing us to travel to Leipzig. There, then, was the annual trade-show, and from there, if possible, we should travel home. If impossible, then we should go to Frankfurt on the Oder, where we had relatives. Right away, early the next morning, we started our journey. We planned to reach Bayreuth by nightfall. That same evening we succeeded to reach the last village before Bayreuth. There, in front of his inn stood the landlord. He advised us not to go any further as a thunderstorm was approaching. We thanked him for his good advice and, as we believed that he wanted us to become paying guests, we continued on our journey. We had hardly walked for another one and a quarter hours when the weather burst upon us with all its fierceness. It had become so dark that we strayed from the road and found ourselves in a little forest in which trees had been dug up. We stumbled into holes and were up to our waist in water. Besides being soaked through from falling into the holes, the cloud burst drenched us from the top. We were lost for quite a while when at last we noticed a light in the distance. We hurried there. When we came closer we found it was a guest house where lively music was playing. The landlady, who met us in the hall, refused to let us in. She had no room for us and besides there wouldn't be any quiet, as they were celebrating a wedding which would last all night. She suggested that we walk on some distance where we could stay at the "Fantasy." There we would find a restful night. The "Fantasy" is an entertainment center not far from Bayreuth. When we arrived there we found the landlord all alone because his family was in town and he had no guests. We were, as mentioned before, completely drenched. I asked the landlord to heat the oven. He obliged. As there was nothing else prepared, I ordered bread, butter and a glass of beer. My brother Leopold did not want to eat anything. He preferred to warm himself. I had hardly started to eat a few bites when I heard a crash. I turned around and saw my brother lying on the floor. He was unconscious. I called the landlord and asked him to call a doctor. We carried my unconscious brother one flight up into a room. We undressed him and had to cut his boots off his feet. [The story ends here.]

[N.B. Moses and his younger brother, Leopold, eventually settled in Prague where they successfully established the first local factory to manufacture cotton cloth. Until then, cotton cloth had been imported from England. For this, in 1841, the brothers were knighted by Kaiser Franz Joseph I, Emperor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Emperor of Germany. Henceforth these two brothers were known by the title Edler (Sir) von Portheim. Leopold became an extremely wealthy man. He was the great-great-grand-father of the translator, Arnold Von der Porten.] Arnold Von der Porten is the author of "The Nine Lives of Arnold"

More about Jacob Frank and the Frankists, here |

|||||||||